Many pathogens must at least transiently infect a host organism to complete one or more stages of their life stages, and many are able to establish long-term persistent infections. Foreign antigens are quickly and efficiently targeted by the host immune system, so in order to survive in this harsh environment, pathogens have evolved various ways to circumvent or disarm these defenses. Because the adaptive immune system uses a complex and time-consuming clonal selection process to develop cell lines with high binding specificity to the presented antigens, one way to temporarily outpace immune surveillance is to continually vary the conformation of antigenic determinants. For this strategy to work, the pathogen must present a tightly controlled antigenic profile to the host and maintain the ability to introduce antigenically distinct variants at regular intervals. In general mutation rates found in typical genomic sequences are insufficient to introduce enough variability to prevent formation of cross-reactive antibodies and immunity. Consequently a number of mechanisms have evolved that tend to promote localized variation within genes coding for immunodominant surface proteins.

These mechanisms can be roughly divided into two categories: random variation and programmed variation (antigenic variation sensu stricto).

Random or unprogrammed variation takes advantage of imperfections in DNA repair and replication processes to introduce variation. Certain nucleotide combinations are likely to lead to induction of error-prone polymerases with a higher probability of point mutations and indels. Other factors increase the likelihood of double-stranded breaks, which when resolved can lead or transfer of stretches of DNA or even entire genes to other regions of the genome.

Programmed variation refers to the existence of specific mechanisms to generate gene diversity. This generally implies a family of paralogous genes encoding proteins with the same or similar functions and the ability to express only one of the family members at a time. In effect this is achieved by maintaining only one active promoter at a time and/or moving genes to a position downstream of an active promoter. This can be accomplished either through recombination or through in situ control:

- Inversion

- Reciprocal recombination

- Gene conversion (cassette mechanism)

- Deletion (preceded by gene conversion)

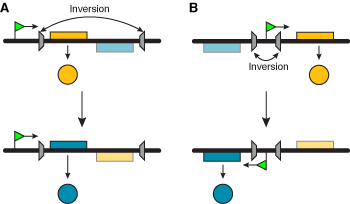

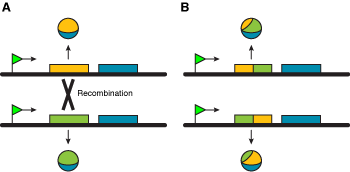

This is the simplest way to move genes relative to a fixed location, and can involve either gene or promoter inversion (Figure 1). The inversion is catalyzed by a site-specific DNA recombinase that recognizes a short DNA segment flanking both sides of the invertible segment. A more sophisticated mechanism involves several segments that can be rearranged in different ways, yielding different products (Figure 2).

|

Figure 1. Mechanism for antigenic variation based on sequence inversion. Gene inversion (A) changes the sequence directly downstream of the promoter. Promoter inversion (B) changes the orientation of the promoter, thereby changing the active gene sequence. The grey symbols represent triggers for the inversion mechanisms. |

|

Figure 2.Complex mechanisms based on gene inversion. The arrangement in (A) can be changed in two ways (B, C), allowing different genes to be transcribed. |

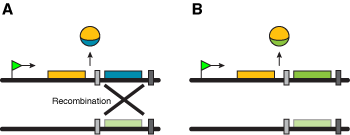

Reciprocal recombination is used for genes near the telomeres (Figure 3), providing a versatile mechanism in pathogens with large numbers of chromosomes or linear plasmids, e.g. trypanosomes, Pneumocystis and Borrelia.

|

Figure 3. The two chromosomes in (A) encode different polypeptides. A recombination event ocurring in the first exon allows the generation of diversity (B). |

Also known as the cassette mechanism, as a gene is inserted behind a single promoter in an expression site like a cassette inserted into a tape recorder. The first cassette mechanism described involved a site-specific endonuclease, but whether a dedicated endonuclease is also involved in antigenic variation in African trypanosomes, the pathogen using this mechanism most extensively, is under debate. The high rate of switching and the limited sequence homology available for gene conversion suggests, but does not prove, the involvement of a dedicated endonuclease, but this enzyme remains to be found.

|

Figure 4. The gene (or a single exon in mammalian genomes) in (A) can be exchanged for a different copy found in a repository location, changing the way the gene is expressed (B). |

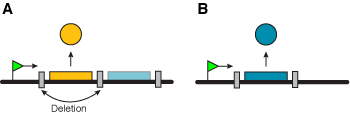

Found in Borrelia, this mechanism requires arrays of antigen genes to be inserted into an active expression site through recombination. If each gene is followed by a strong transcriptional stop, removing the first gene in the array by deletion thereby activates the second one. Such mechanisms can work only if antigen genes are introduced into the expression site in an asymmetrical fashion, i.e. an array of genes replacing a single gene. Otherwise, the gene would be entirely lost from the genome and the gene repertoire would rapidly shrink.

|

Figure 5. Only the gene immediately downstream of the promoter region is transcribed (A). A deletion event provokes a change in the expressed gene (B). |

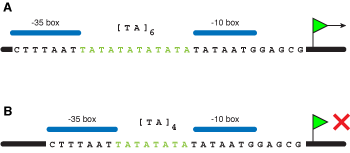

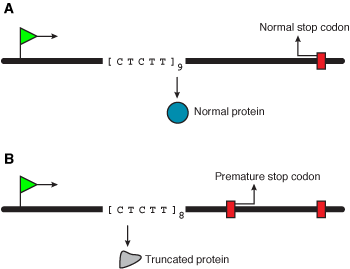

Varying the length of simple repeat tracts allows control of gene expression at the transcriptional (Figure 6) and translational levels (Figure 7).

|

Figure 6. Transcriptional regulation of gene expression involves a change in the distance between elements in the promoter region. This prevents the correct binding of transcription factors or the RNA Polymerase, blocking expression of the encoded gene. |

|

Figure 7. Translational control of gene expression involves a change in the length of a short repeat sequence in the coding region. This change generates a premature stop codon, resulting in a non-functional protein. |